The Principles of Environmental Justice

A chain reaction. Ripples in a pond. The domino effect.

That’s how you might describe what followed Dr. Robert Bullard’s research in 1970s Houston. Known as “the father of environmental justice,” he began collecting data around a lawsuit (Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management Corp.), trying to discern whether the placement of a municipal landfill in a predominantly African American community was truly random or part of a pattern.

Here’s what he found: even though Black Houstonians only made up 25 percent of the city, 82 percent of all waste was dumped in their neighborhoods. This is an example of environmental injustice, and it doesn’t stop there.

Take the “zip code vs. genetic code” dilemma. In 2019, Time Magazine reported a 30-year difference in life expectancy for residents of Chicago, Illinois. The residents in question lived only miles apart.

“Your zip code is the greatest predictor of how long you are expected to live. Not your blood pressure, not your cholesterol levels, not your genetics. Your zip code.”

– Jamie DuCharme and Elijah Wolfson, Time Magazine

From air pollution and toxin exposure to accessibility of healthy food, green space, and medical care, where you live drastically affects your health outcomes. More importantly, the cities with the widest gaps in life expectancy, the researchers found, were those that were most segregated by race and ethnicity. So, it’s no surprise that a pattern has emerged since Dr. Bullard’s early research: Environmental racism is not accidental.

Understanding climate change and environmental justice

Environmental justice refers to the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all individuals—regardless of their race, national origin, or income—in developing, implementing, and enforcing environmental laws and regulations. Part of environmental justice is recognizing that certain communities, particularly marginalized and low-income groups, disproportionately bear the burden of environmental pollution and hazards.

According to Dr. Bullard, true environmental justice would mean the people who benefit most from industrial growth also share in the burdens of its hazards and health impacts.

“The first principle of environmental justice is: People who are most impacted must be in the room and at the table to speak for themselves,” said Bullard. “It’s common sense that you would get those individuals and institutions to talk about how we’re going to go forward as opposed to planning with some diplomats who have never lived close to the problem.”

“The problem,” in this case, lies much deeper than municipal waste sites. The reality of environmental sustainability is that it’s inextricable from social sustainability, which takes into account systemic inequalities to ensure everyone has access to the same opportunities and outcomes (regardless of zip code, for example). In fact, all three pillars of sustainable development are inextricably linked. They serve as a framework that promotes long-term well-being for the planet and the present and future generations living on it—but only if those pillars are balanced.

The history of environmental justice

- 1968: The Memphis Sanitation Strike was the first time African Americans mobilized on a national level to oppose environmental injustices.

- 1979: A group of homeowners in Houston, Texas formed the Northeast Community Action Group (NECAG) to fight against a landfill being placed within 1,500 feet of a public school and brought it to court. While Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management Inc. failed to prevent the landfill’s construction, it sent a clear message for environmental justice cases country-wide.

- 1982: The Warren County North Carolina PCB Landfill Sit-In is widely recognized as the catalyst for the environmental justice movement. More than 500 environmentalists and civil rights activists were arrested during this nonviolent protest.

- 1983: Dr. Robert Bullard conducts a study—the first of its kind—mapping the locations of Houston municipal waste facilities. He then published “Solid Waste Sites and the Houston Black Community,” which was the first comprehensive account of environmental racism in the United States.

- 1987: Toxic Waste in the United States (a document released by the United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice) analyzes the relationship between the location of a hazardous waste site and the racial and socioeconomic composition of those communities.

- 1988: WE ACT (West Harlem Environmental Action) was founded and evolved into New York’s first environmental justice organization dedicated to environmental and health quality in communities of color.

- 1990: The grassroots Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) is formed to build the capacity of indigenous communities and governments to protect the sacred sites, land, water, air, natural resources, and health of their people and all living things. 1990 also saw the Congressional Black Caucus meeting with EPA officials, the formation of the Environmental Equity Workgroup, and the publishing of the first book focused primarily on documenting environmental injustice: Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality.

- 1991: The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit was held in Washington, D.C., where the 17 principles of environmental justice are penned.

The principles of environmental justice

Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to U.S. Congress, once said, “If they don't give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

In the fight for climate justice, that’s exactly what marginalized communities did. On October 24, 1991, nearly 300 Black, Native, Latino, Pacific Islander, Asian American, and other minority activists gathered in Washington, D.C. to discuss, for the first time in history, the environmental injustices their communities were experiencing. Over four intense days, 17 principles of environmental justice were drafted at the National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit.

Overarchingly, the principles are a call to action — a list of demands to achieve true climate justice:

- Increasing ecological protection and safety within disadvantaged communities

- Expanding cultural awareness and addressing potential language barriers

- Promoting environmental education

- Providing additional opportunities for everyone to participate in the decision-making process, regardless of race or socioeconomic status

Those are the principles, but why do they matter?

Because environmental justice is a human right, and it aligns with the fundamental rights of all individuals.

Let’s explore some of the overarching themes of the principles of environmental justice.

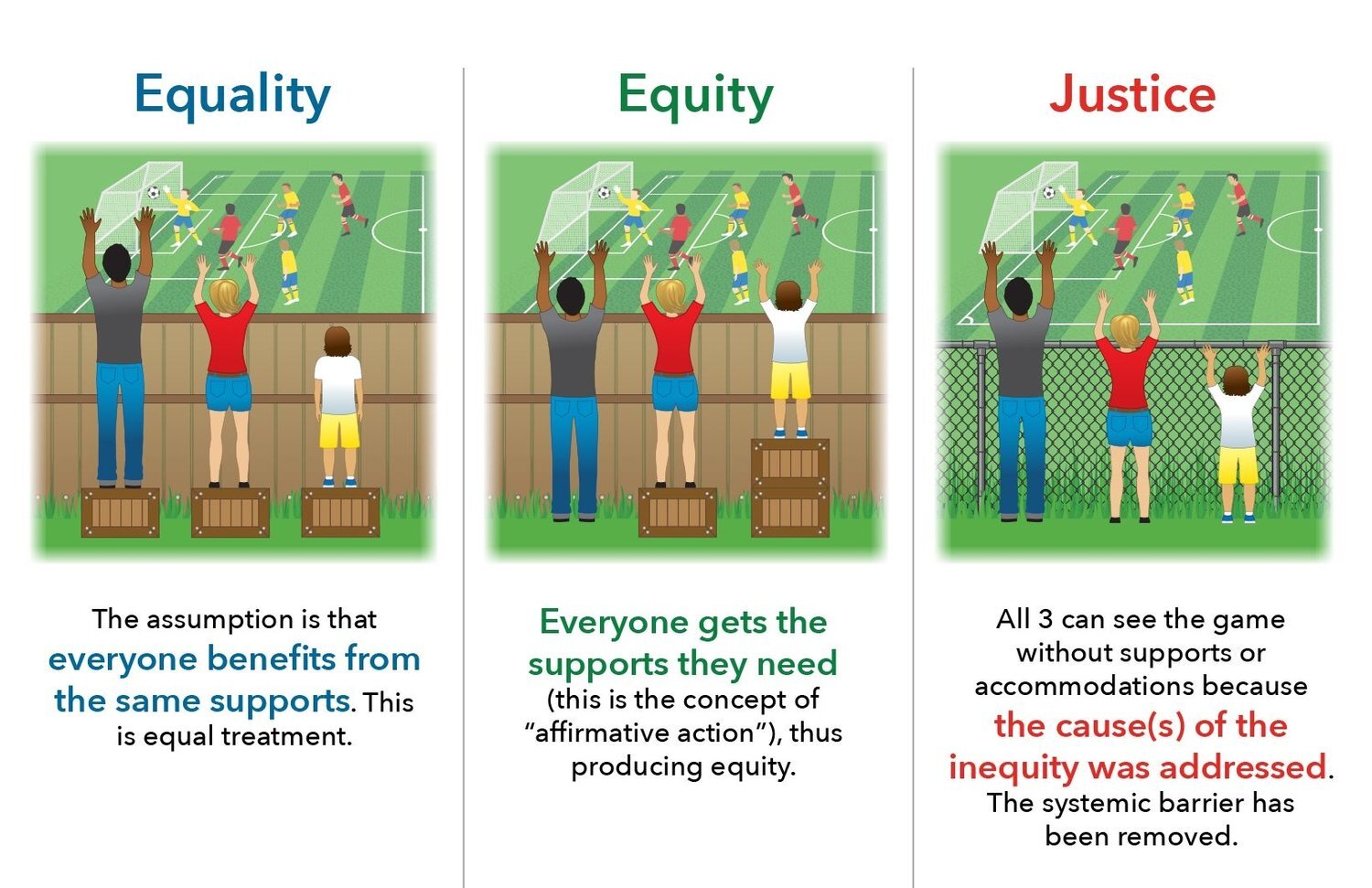

Equity

In the age of information, environmental justice runs the risk of being a buzzword. This has caused many journalists, activists, and members of the public to use the terms “environmental justice” and “environmental equity” interchangeably.

In reality, they aren’t interchangeable. If “environmental equity” is a fundamental human right, environmental justice is the act of protecting that right.

The distinction between justice and equity matters, especially considering principle #2 of environmental justice—that public policy must be based on mutual respect and justice for all people.

Participation

Where there’s a will, there’s a way — especially when it comes to environmental justice principle #5.

The Will: There is a fundamental right to political, economic, cultural, and environmental self-determination for all peoples. In other words — there is a need for inclusive decision-making processes and environmental justice.

The Way: Participatory justice, or the direct participation of those affected most by a particular decision in the decision-making process itself.

According to WE ACT for Environmental Justice, there are methods using participatory justice to empower marginalized communities in policy-making and planning:

- Create spaces for research-sharing and networking between communities

- Critically evaluate who benefits from decisions being made by your group

- Center guidance, input, and feedback from leaders of frontline communities

- Make meaningful diversification a part of “the work”

Practice and Prevention

Adopting sustainable practices is necessary if we’re going to have a future that's equitable for all, including:

- The cessation of the production of all toxins and hazardous waste

- Making choices as consumers to consume as little of the Earth’s resources as possible.

- Taking preventive measures to protect communities and the environment, especially Environmental justice interventions

- Using climate science to inform action

- Education of present and future generations, which emphasizes social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives

The environmental justice movement and Bard

The environmental justice movement requires all of us, and no role is too small.

The Graduate Programs in Sustainability at Bard empower environmental justice champions through transformative degree programs where sustainability is baked in, not bolted on. Whether you are looking for environmental justice jobs or are just embarking on your environmental justice journey, we have four tracks for you:

- Master’s in Environmental Policy

- Master’s in Climate Science and Policy

- MBA in Sustainability

- Master’s in Environmental Education

If you’re interested in joining the movement and becoming an agent of change, learn more about the state of environmental justice.

-891746-edited.jpg?width=365&name=PROOF_PM_BardMBA_NYC_05-13-16_MG_3854_PROOF(1)-891746-edited.jpg)